Research by Kenan Arifoğlu (UCL School of Management) and Chris Tang (UCLA Anderson) suggests a system of manufacturer rewards and penalties, consumer taxes and subsidies could aid vaccination rates.

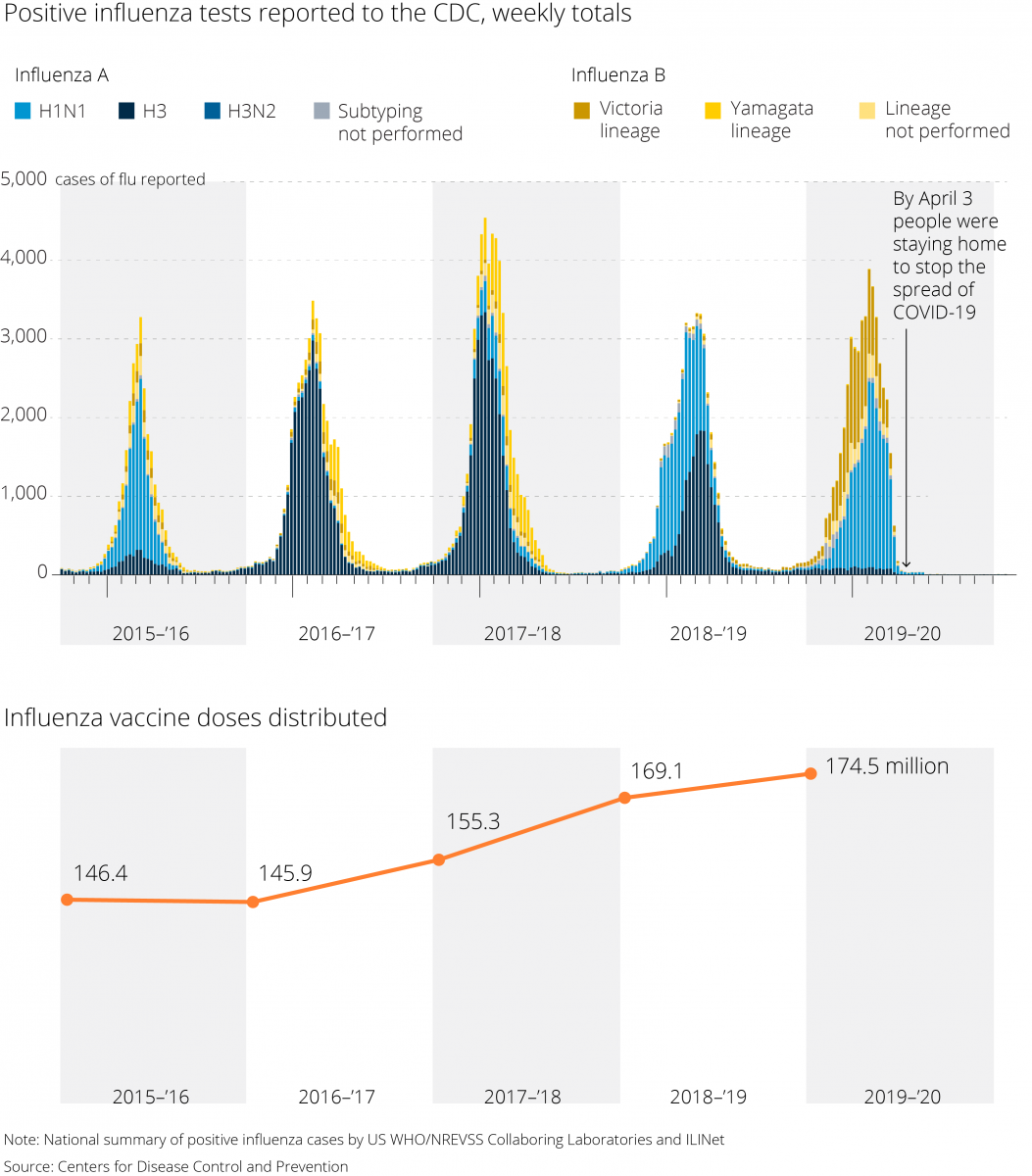

A mostly laissez-faire approach to the production and administering of flu vaccines in the U.S. manages to make nearly 200 million doses available a year. But compliance with Centers for Disease Control and Prevention guidelines that most people 6 months or older be vaccinated is poor: Only about 45% of adults were vaccinated in the 2018-19 season, somewhat higher than the 37% of the previous year.

This, despite the fact that the flu is one of the world’s deadliest infectious diseases, killing as many as 646,000 people a year. In the worst recent outbreak, more than 79,000 people in the U.S. died from flu-related illnesses in the 2017-18 season.

There are several different types of Influenza viruses, and they mutate constantly, with new strains appearing every year. For instance, different strains of H1N1 virus appear regularly; commonly known as swine flu, a version was responsible for a 2009 pandemic. Each year, epidemiologists forecast the strains likely to be most common in the coming season, and flu vaccines are designed to target multiple strains. This year, all regular-dose flu vaccines are quadrivalent, meaning they’re designed to protect against four different flu strains.

Now, as the world heads toward year two of the COVID-19 pandemic, the last thing anyone needs is a major flu outbreak. That may explain why fears of a “twindemic” have led to an early rush for influenza vaccines, with some local shortages around the U.S.

The CDC says there’s no national scarcity, and large pharmacy chains say they will have enough doses for the season. Still, even in a normal year, matching supply and demand for flu vaccines is a challenging problem.

Given the low vaccination rates in the U.S., manufacturers don’t want to risk over-producing and getting stuck with a huge stock of worthless doses at the end of the season. And while serious shortages are rare, when they do occur, they can mean a lack of vaccines for those at highest risk from the disease, such as the very young, pregnant women and the very old.

The U.S., which relies on market forces, lacks a comprehensive strategy to ensure that sufficient vaccine supplies are available and that everyone has access to them.

A paper forthcoming in Manufacturing & Service Operations Management by UCL School of Management’s Kenan Arifoğlu and UCLA Anderson’s Christopher Tang proposes an incentive program designed to boost demand for the flu vaccine, ensure its supply and match those two forces during the inevitable ups and downs of deliveries. The plan would make vaccines easier and cheaper to obtain when supplies are abundant and deliver subsidies to manufacturers to make sure they are. When shortages occur, vaccine makers would be penalized, and consumer subsidies would be available only to high-risk individuals.

The proposed incentive plan, the authors say, could reduce the social costs of a flu outbreak — from treatment, hospitalization and lost wages — by more than 70%.

“To balance supply and demand for flu vaccines, the government needs to develop reward and penalty mechanisms to align the incentive between pharma and the public,” Tang said in an interview. Supplies of the vaccines have steadily risen in recent years, and manufacturers project they will produce as many as 198 million doses this year, the CDC says. Actual vaccine production is uncertain since it depends in part on how successfully flu viruses can be grown in millions of chicken eggs. Other disruptions can occur; a severe shortage in 2004 resulted when British authorities halted production because of bacterial contamination at a vaccine plant, cutting U.S. supplies by half.

Because of uncertainty about supplies and public demand, inefficiencies in the vaccine supply chain can result in more people getting sick and some dying as the vaccine both protects the recipient and helps limit the spread of the disease.

Arifoğlu’s and Tang’s incentive program aims to counteract these inefficiencies and maximize the social benefits. To manage demand, the program would include a tax collected with existing Medicare taxes before the flu season. When supplies are plentiful, the funds would spur demand by subsidizing vaccinations through vouchers or payments to health care providers. When shortages occur, the subsidies can be withdrawn or made available only for high-risk patients.

Similarly, on the supply side, a set of transfer payments would reward manufacturers for high production and penalize them when production is too low. Such a payment system could be implemented as part of the CDC’s vaccine contracts program, which places preorders for distribution by public health services.

The study envisions the long-term subsidy costs being covered by penalty payments. Thus, such a program could be revenue neutral, the authors say. What’s more, when the social costs of a flu outbreak are very high, combining demand- and supply-side incentives would significantly reduce those costs.

As the world waits for a COVID-19 vaccine, it’s natural to wonder if such an incentive program could help smooth its rollout, when demand will be uncertain and the need to make sure front-line health workers and the people most at risk are at the front of the line for vaccination.

There are now two Covid-19 vaccines described as highly effective by their developers, though widespread delivery of either is likely months off. There will be strong calls for government to pay for the vaccine — and to ensure plentiful supply — given the public health and economic risks to people not taking the vaccine.

This article was originally written for the UCLA Anderson Review.